Here.

Thursday, July 24, 2025

Monday, July 14, 2025

Navigating the Strait of Leipzig: 5,000 euros in damages to a Meta's end user for processing personal data on third-party websites

From the Strait of Messina, where Scylla and Charybdis lurked, to an imaginary Strait of Leipzig, where a judge has just awarded damages to a Facebook/Instagram (?) user for a GDPR breach that reverberates with much of what was discussed in the marathon post on the DMA Meta 5(2) non-compliance decision (🍎🍏🟠). Not being too put off by the Trockenheit of German legal prose (survived practising and doing research as a young lawyer in Biergärten-full Munich), this ruling is nothing short of thrilling...Why not jotting down a couple of observations?

You Wavesblog Reader are no longer a Spanish Facebook user but a German user not at all enjoying reading gardening websites (your last Bavarian geraniums died off long ago, with no regrets) but you have an health issue (sorry for that!) and spend a lot of time surfing the Internet and spending time specifically on websites like apotheken.de, shopapotheke. de, docmorris.de, aerzte.de, helios-gesundheit.de, jameda.de (You tried out ChatGPT too but are far from trusting its advice).

Thursday, July 03, 2025

Targeted advertising by Meta democratised advertising and made people love ads (so we heard): discuss

Meta DMA enforcement/compliance workshop, video here.

Thursday, June 19, 2025

DMA (Team) Sudans, when will Meta's compliance with Article 5(2) finally flow?

|

| Don't look for it in Rome... |

Why, then, did it take an 80-page decision, and why is Meta, in all likelihood, still not compliant more than a year after it was first required to be? The most obvious answer, of course, is that the obligation in question strikes at the very heart of Meta’s business model, not only as it stands today, but also with implications for future developments, given the EU legislator's insistence on DMA compliance by design, a theme that has been a recurring one here on Wavesblog. Moreover, in this case, the Commission is not simply tasked with interpreting and enforcing a 'standard' DMA obligation in relative isolation; to do so, it must also apply the General Data Protection Regulation in conjunction with the DMA. That these two legislative instruments converge in more than one respect is also confirmed by the German ruling mentioned earlier and to which we shall return in due course. On that note, we are still awaiting the joint EDPB/Commission guidance on the interplay between the DMA and the GDPR, which, according to Commission’s remarks this week in Gdańsk, is expected imminently. Interestingly, the Commission takes this into account as a mitigating factor in determining the fine for non-compliance ("the Commission acknowledges that the interplay between Regulation (EU) 2022/1925 and Regulation (EU) 2016/679 created a multifaceted regulatory environment and added complexity for Meta to design its advertising model in a manner compliant with both regulations"). That might be perfectly understandable, were it not for the fact that we are, after all, dealing with Meta, which has elevated non-compliance with the GDPR to something of an art form worthy of Bernini. This raises both a puzzle and a question: will Meta be left to do much the same under the DMA? And might other gatekeepers be allowed to match, or even surpass, it? Is there, perhaps, a structural flaw in the DMA’s enforcement apparatus, just as there are, quite plainly, in the GDPR, that gatekeepers can be expected to exploit at every opportunity? Or is it simply a matter of DMA enforcement resources falling well short of what would actually be required? What, then, can be inferred from this particular decision in response to that question? Serious reflection is clearly needed here. For now, I can offer you, Wavesblog Readers, only a few very first impressions, but I’d be all the more keen to hear yours.

Even before Compliance Day (7 March 2024), it is clear from the decision that the Commission already had serious reservations about the "Consent or Pay" advertising model that Meta was in the process of grinding out, which had been presented to the Commission as early as 7 September 2023. The decision makes clear not only that the Commission was in close dialogue with Meta, but also that it engaged with several consumer associations and other interested third parties, on both the DMA and privacy sides of the matter. On that note, a further question, though perhaps it’s only me. Should there not be, if not a formal transparency requirement then at least a Kantian one, for the Commission to list, even in a footnote, all the interested parties with whom it bilaterally discussed the matter? On this point, one almost hears the Commission suggesting that such a transparency obligation might discourage others from speaking up, for fear of retaliation by the gatekeeper. The point is well taken, but one wonders whether some form of protected channel might be devised, a kind of "privileged observer’s window with shielding" available where reasonably requested, providing clear assurances that the identities of those coming forward will be safeguarded (short of being a whistleblower). Moreover, as is well known, this point tangentially touches on a broader issue. The EU legislator, likely with a view to streamlining enforcement, left limited formal room for well-meaning third-party involvement. The Commission-initiated compliance workshops, the 2025 edition of which has just begun, are a welcome addition, but they are, of course, far from sufficient. In particular, without access to fresh data provided by the gatekeepers, available only to the Commission, how are third parties expected to contribute anything genuinely useful at this point of the "compliance journey"? As we shall see, this concrete data was also an important point in the very process that led to the adoption of the non-compliance decision in this case (Meta knew that its 'compliance model' was producing exactly the result they wanted). The lawyers, economists and technologists on the DMA team have clearly had their hands full in the matching ring with Meta (hence, of course, the Sudans in the title). Even a quick reading of the decision reveals, between the lines and squarely on them, the array of tactics deployed by Meta to throw a spanner in the works of effective DMA compliance, all carefully orchestrated and calculated with precision, and surprising no one. But one does wonder whether the DMA’s hat might not still conceal other tools, better suited to crowdsourcing and channelling constructive efforts, particularly from those third parties who stand to benefit from the DMA (as we also heard in Gdańsk), from conflict-free academics, and from what might be called real civil society, genuinely committed to effective and resolute DMA enforcement, rather than the usual crop of gatekeeper-supported associations.

|

| Data cocktails beyond the decision |

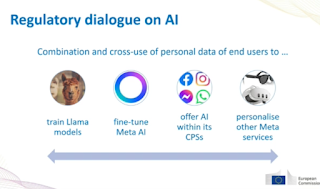

Perhaps the best place to restart is with what was clearly explained during the Compliance Workshop, and you, dear Wavesblog readers, who’ve perhaps already pored over the decision, will have caught all the nuances of it. The non-compliance decision at issue concerns a single type of data combination covered by Article 5(2). Many other cocktails Meta shakes up with your data fall outside the decision’s direct scope, but are still covered by the same article and have been extensively discussed in the ongoing regulatory dialogue between the DMA Team and Meta. Data cocktails can be mixed within CPSs themselves (e.g., Facebook and Messanger), but also between CPSs and the gatekeeper’s other services (e.g., Instagram and Threads). During the workshop, we heard from the Commission that these other 5(2)-related compliance discussions largely centred on what qualifies as an equivalent service for users opting out of data combination, without slipping into degradation beyond what’s strictly necessary due to reduced data use. These, as we understood, are discussions about the kind of service a user who declines data combination is entitled to expect, and whether it is genuinely equivalent, as required by Article 5(2). In this context, it emerged that the Commission and Meta have been discussing what such a service looks like. For example, Messenger or Threads when data combination with Facebook and Instagram, respectively, is not allowed by the end user. On this front, the Commission noted, with some satisfaction, that improvements have been made.

|

| Source: Proton Drive on X |

|

| End user's journey: 1.0 |

|

| Penelope waiting, Chiusi Etruscan Museum |

Based on the Commission's reading of Article 5(2) DMA, the legal reasoning underpinning the non-compliance decision is twofold. First of all, the less personalised but paying (Scylla) and the fully personalised (Charybdis) options cannot be considered equivalent alternatives, as they exhibit different conditions of access. Second, the binary configuration of Meta’s consent-or-pay model (Scylla or Charybdis) doesn’t ensure that end users freely give consent to the personalised ads option, falling short of the GDPR requirements for the combination of personal data for that purpose. But what about ('data combination in Meta's advertising services') 2.0? In November 2024, Meta charted an additional ads option. This is a free of charge, advertising-based version of Instagram and Facebook. Further tweaks to this option followed just as the 60-day compliance period set out in the non-compliance decision was about to expire — enter 3.0. Is it finally the Ithaca Option, that ensures compliance with the DMA by giving the end user a real chance to exercise the data right enshrined in Article 5(2)? In its non-compliance decision, specifically on Meta’s data combination 1.0, the Commission, without delving into detail, also indicates what a DMA-compliant solution would, in its view, require, making explicit reference to elements introduced in 2.0:

1) the end user should be presented with a neutral choice with regard to the combination of personal data for ads so that he/she can make a free decision in this respect;

Before diving into the more legal aspects of the non-compliance decision, while taking on board, too, at least some of the arguments aired by Meta during the workshop (soon to be set out in more precise legal terms in the upcoming appeal against the decision), I’d like to surf briefly above the currents of DMA enforcement. Allow me, dear Wavesblog Reader, a quick self-quotation (then I’ll stop, promise). Reflecting on Article 5(2) and other DMA data-related provisions in something I wrote in early in 2021, I reached a conclusion I still stand by, namely that this provision, at its core, and with regard to online advertising specifically, should provide end users with a real choice over the level of ‘creepiness’ they’re comfortable with. That may sound rather underwhelming — and it is. In fact, in the same piece, I wondered whether it wasn’t finally time to regulate personalised advertising more broadly, and for real, without losing sight of the broader picture: that private digital infrastructures, especially informational ones, ought, depending on the case, to be regulated decisively, dismantled, made interoperable, and so. At the same time, I do believe this end user's right to choose as carved clearly into Article 5(2) of the DMA, without tying it to one’s capacity to pay in order to escape a level of surveillance one finds uncomfortable (for oneself and/or the society she/he lives in), is immensely important.

|

| Bravissima, whatever. |

It’s a glimpse of something different: a very narrow but real incentive in favour of an "economic engine of tech" that starts rewarding services built around data minimisation and not surveillance and data collection (and its combination). From this perspective, offering the mass of Facebook and Instagram users a genuinely neutral choice, and thus the concrete possibility of making a free decision in favour of a less, but equivalent, personalised alternative (e.g., about the preferred level of creepiness), could also have a welcome educational effect. However, we can’t pretend that the current AI age hasn’t, for now at least, further accelerated the shift towards surveillance and data accumulation — and what’s being done to counter it still feels far too limited (see also the above-mentioned ruling by the Cologne court).

|

| Hannibal in Italy, Palazzo dei Conservatori - Rome (incidentally, where the Treaty of Rome was signed in 1957) |

|

| Distinct legal notions |

As just noted, the enforcement of the DMA is not necessarily bound by the contours of the GDPR where the DMA goes beyond it, or simply moves in a different direction. However, for those parts where the EU legislator has drawn on legal concepts from the GDPR, such as the requirement that end users give valid consent to the combination of their personal data for the purpose of serving personalised advertisements, reference must be made to Article 4(11) and Article 7 of the GDPR. This, in turn, triggers a duty of sincere cooperation with the supervisory authorities responsible for monitoring the application of that Regulation. Here, however, a possible complication arises, which in the ideal world of EU law enforcement perhaps shouldn’t exist. And yet, it does. We won’t dwell on it for long, but it’s worth highlighting (and it may at least partly explain Mario Draghi’s well-documented allergy to the GDPR, reaffirmed only a few days ago). The cast of characters on the GDPR enforcement stage has often found it difficult to offer a consistent reading of this Regulation. Unsurprisingly, this has weakened enforcement and worked to the advantage of those less inclined to embrace it. This risk has been avoided under the DMA, notably by assigning quasi-exclusive enforcement power to a single entity: the Commission (though arguably creating others in the process, which we won’t go into here). Echoes of the considerable effort supervisory authorities expend to ensure even a modicum of consistent GDPR application also surface in the text of the DMA non-compliance decision, where the Commission finds itself almost compelled to justify having taken into account the EDPB’s opinion on the matter when applying the GDPR (e.g., explaining that "the fact that some members of the Board voted differently or expressed reservations about the Opinion 08/2024 does not diminish the value of that Opinion, in the same way that the Court’s judgments produce their effects irrespective of whether they were decided by majority or unanimously"). What matters is that DMA enforcement not be delayed or undermined by such tensions, which, one imagines, some gatekeepers could hope to exploit, should a tempting opportunity arise.

|

| Series 1 |

As a Facebook user living in Spain and enjoying gardening pages, under the DMA you must be presented with a “specific choice” as to whether you wish to allow the combination of data from your Facebook environment with data from Meta Ads. This choice involves two key elements: first, Meta must offer you an alternative version of Facebook that is less personalised, namely one that does not entail combining your data across these two services. Of course, you’d still be very likely served ads, just not extremely targeted ones based on the precise profile Meta has of you, possibly built over many years of Facebook use. Your experience in the Facebook environment would then be less creepy, if you ever happened to feel it that way. Second, this Facebook alternative must be equivalent to the Facebook version based on data combination. This reveals rather strikingly the clear distance between what is required by the EU legislator and the solution instead put together by Meta through the consent-or-pay advertising model, which is the subject of the non-compliance decision. Meta did not offer you the choice of an equivalent but less creepy service, if that is something you care about. What you were offered instead was a version of Facebook with no ads but behind a paywall, and therefore, according to the Commission, not something you could reasonably perceive as equivalent to the unpaid version, and thus you weren't presented with a genuine choice between the two. In fact, the Scylla/pay option entails an economic burden for you, Facebook user living in Spain who has recently visited gardening websites, as the amount paid cannot be spent on other items. The Charybdis option, by contrast, avoids this burden, allowing you to consent to the processing of your personal data in exchange for access to additional services. In addition to the economic burden, further inconveniences make Scylla even less appealing than simply clicking a button to consent to data combination. You may not have access to an online payment service (which not everyone does), and even if you do, entering your payment details into Meta’s system is plainly far less straightforward than simply clicking a button and move on with your life. Moreover, the Commission notes that you have, perhaps for years, been accustomed to using Facebook without any monetary payment, and that it is difficult for you to assign a clear price value to the 'Facebook environment.' Here, the Commission directly addresses a point we’ve also heard from Meta during the public compliance workshop: the so-called YouTube argument. I don’t know about you, dear Facebook user, but I have a YouTube Premium subscription: I find ads particularly disruptive, especially when I’m deep into a good on-demand webinar on the DMA or an informative, in-depth documentary about Scipio Africanus). You, on the other hand (and I wouldn’t know personally, having never used Facebook myself, as I never quite saw the point as it was initially marketed - if I really lost touch with schoolmates and acquaintances, there was probably a reason), have apparently grown accustomed to the display of advertisements as such (not necessarily personalised ads, mind you), and therefore may not perceive them as being particularly disruptive. Hence, the option of no advertisements for a fee does not appear as attractive to you as to me as YouTube user.

And here the Commission goes straight to a point that, by this stage, could hardly be ignored: we “end users of online services overall have a low willingness to pay for privacy, even when [we] would prefer a less personalised experience.” Meta knew this perfectly well, as also shown by the "empirical evidence provided in the academic studies which are cited in Meta’s submissions." Moreover, documents in the case file indicate that Meta actively relied on this specific insight to calibrate the pricing strategy of the ‘Subscription for No Ads’ (SNA) option with a clear objective in mind: "that end users would not exercise their specific choice." And in this, Meta certainly achieved its objective, as “Meta’s own estimation prior to the launch of the SNA option was therefore very close to the actual [miserable] take-up rate.” Therefore, the Commission concludes, "it is evident that Meta not only should have known, but that it actually knew, that the different conditions of access to the Facebook and Instagram environments under the SNA option do not offer end users an equivalent alternative to the With Ads option and that launching the SNA option would deprive its Non Ads Services end users from the specific choice to which they are entitled pursuant to Article 5(2), first subparagraph, of Regulation (EU) 2022/1925."

The decision also reveals an interesting exchange between Meta and the Commission on whether the conditions of access should be regarded as a fundamental feature of the Facebook or Instagram service, such that, if those conditions differ, the services can no longer be considered equivalent. Let’s take a simple example. Choosing between a red apple and a green apple? That’s clearly a choice between equivalent options: still apples, after all. Choosing between an apple and an orange? Arguably, not equivalent. But what if the choice is between paying €1 for a red apple, or getting a green apple for free, on condition that someone records you eating it? Is it still, unavoidably, a choice between two equivalent options? On this point, the Commission is unequivocal: "The means of remunerating the services by the end user are relevant because they are a fundamental characteristic of such services which influence the end users’ choice of whether to use them." The logical conclusion, at this point, is that equivalence between the services from the point of view of the conditions of access would require that both apples are remunerated either with money or with data. And here too, the Commission is unequivocal: “if Meta decides, when exercising its freedom to conduct its business in a manner it sees fit, to offer the With Ads option free of monetary charge, then it is required to offer end users a less personalised alternative which is equivalently free of monetary charge.” Does this also mean that, at some point, Meta could legitimately present you, Facebook user based in Spain with a passion for gardening pages, with a DMA-compliant choice between a With Ads option at €1 or less per month and a Facebook experience free of personalised advertising at €10 or more? Is that where we’re heading? Is it enough to consider this option unlikely simply by acknowledging that even one euro, or much less, might be enough to put you off using the Instagram or Facebook service? And since Meta knows this perfectly well, isn’t that precisely why it would never go down that road? What we do know is that, for now at least, Meta isn’t — at least not if one looks at its Compliance Solutions 2.0 and 3.0.

To close this very long blog post, it’s worth trying to end on a constructive note. The Commission has spent a great deal of time dismantling each of Meta’s legal arguments. But what have we actually learned about the substantive content of this precious end-user right? I would imagine that, in the course of the intense regulatory dialogue between the Commission and Meta, fairly specific indications were discussed at some point, though these surface only in part from the non-compliance decision. But let’s try to distil what can be reasonably be gleaned. First of all, it is clear that there must be an alternative to the With Ads option; that this alternative must be less personalised; and that it must be equivalent. As noted above, this is not to say that advertisements cannot be shown to end-users of the Facebook and Instagram environments — but serving those advertisements must not involve the combination with personal data from Meta Ads. Second, with regard to the requirement of equivalence to the service offered to users who consent to the With Ads option: the only permitted difference lies in the amount of personal data used to provide the service and serve ads. In all other respects, the service must be equivalent, such as, for example, in terms of performance, experience, and conditions of access. From the end-user’s perspective, one may therefore reasonably question whether the option introduced by Meta in November 2024, which brought advertisements in the form of unskippable interruptions across Instagram, Facebook, and integrated services such as dating and gaming, did not in fact degrade the user experience. Based on the slides presented by Meta during the public workshop, there appear to be immediate grounds for doubt on both of these last points.And now, you may well ask, what comes next? A fair question. The Commission is undoubtedly poring over version 3.0, yet because we are testing a brand-new instrument in real time, the path forward is hard to map. At some point the EU courts will have their say on consent or pay as DMA compliance solution under Article 5(2), but, as I noted at the outset, the Commission’s decision looks confidently robust.

-

Fresh off the press release: the Italian antitrust authority has knocked — quite literally — on Meta’s door. A dawn raid hit the company’s ...

-

Aka " From Digital Feudalism to Digital Sovereignty " - UCL IIPP, blog and video here. First of all, I strongly recommend watching...

-

OFE, here.

-

Euractiv, here.

-

T. Davies, here.

-

J.-U. Franck, here.

-

Chez Oles, here .

-

TechCrunch, here.