Monday, July 28, 2025

Fueling US digital exports growth into the EU, you say?

|

One gone, for now, two blissfully absent |

Peacock Tariff Consulting, here.

Friday, July 25, 2025

Boiled by Design: Can Europe Still Save Its Digital Frog (and almost everything else)?

Now, I’d like to offer a few thoughts to set out where, in my view, the key points lie, and how we might frame them in a way that keeps this essential conversation moving in the right direction for the EU and beyond. I won’t begin with the problems, those are already well worn ground for any Wavesblog Reader who isn’t merely passing through. But if you do fall into that latter category, I’d suggest starting with the EuroStack Report itself, if you don't know it already, which came up several times during the panel discussion.

To stack or not to stack - and how?

Thursday, July 24, 2025

Wednesday, July 23, 2025

Martijn Snoep: Antitrust & Industrial Policy. Independence or Coordination. Champions. Latest Cases

|

| Tools available to make markets work |

Impressive, brave interview.

I'm perhaps a bit more positive about the long term impact of the DMA: it's going to evolve (that was the legislators' will), it creates new, important rights for end users and business users, and it is already influencing competition policy in a positive way. But it was never supposed to act in isolation (again, as foreseen by the legislators - see e.g. the HLG). Plenty of potential in many directions...

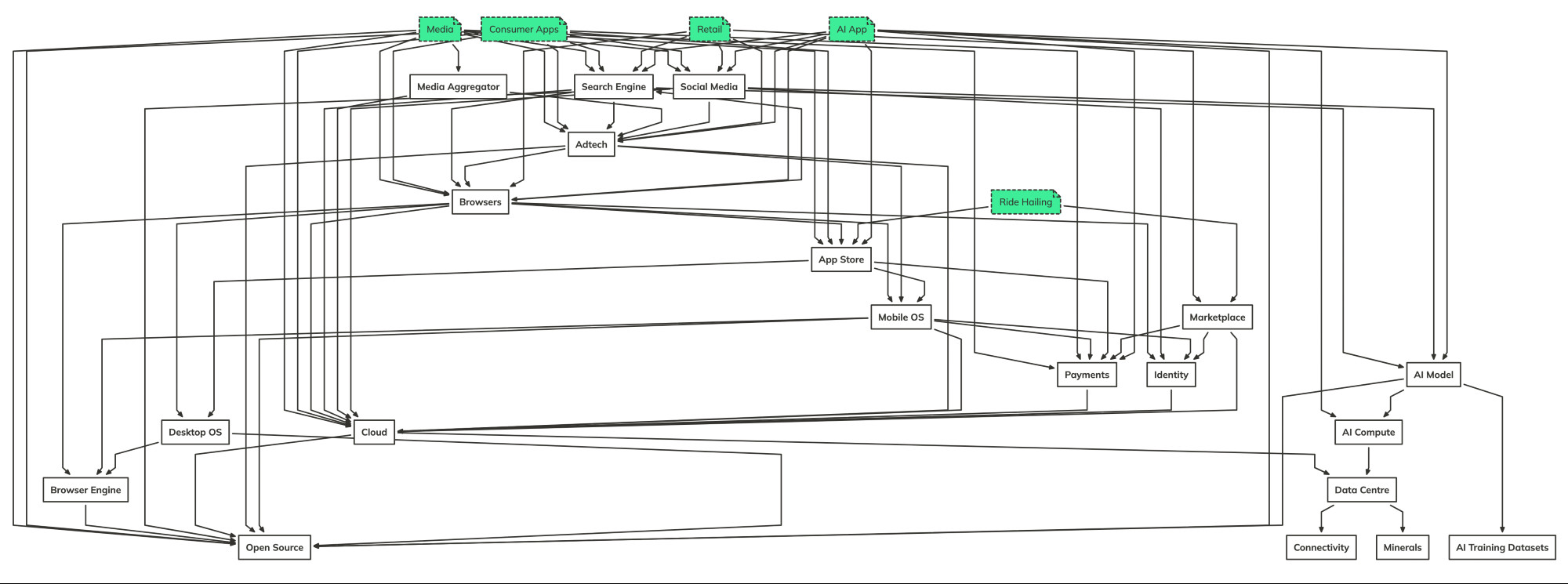

Listening to how the ACM has come to see itself as "market designer," I was reminded of this 2017 "no AI" generated image I used at a conference in Brazil (found back by chance while writing this).

Wednesday, May 21, 2025

Beyond Draghi and Letta: read the #BertrandReport...in a Post!

That said, I’ve always found it a touch odd, if I’m honest, that a banker and a politician, both hailing from a city I adore, albeit a glorious ruin, should be the ones, hand-picked by a German doctor, to tell Europe how to become more innovative ;-).

I'm afraid that, like most articles on this topic, it largely misses the mark.

Which in itself illustrates a key reason why Europe is lagging behind: when you fail to understand the root causes of an issue, you have zero chance to solve it.

What makes me competent to speak on this topic?

Back in the late 2000s and early 2010s, I founded and led HouseTrip which at the time was one of Europe's top startups. We were the first historical startup in which all top 3 VC investors in Europe invested.

So I have a pretty intimate knowledge of the European entrepreneurship ecosystem and what it takes to create and grow a tech company in Europe.

We were pretty promising as a startup. In fact as promising as it can possibly get.

We had a similar concept to Airbnb (with some notable differences I won't bore you with), except we created the company 1 year before they did. Which means we were the first-mover - globally - with a multi-billion-euro concept, strong financial backing by the 3 top investors in Europe and, at some point, a team of 250 people with some of the brightest minds in tech in Europe. Everything we needed to succeed.

And yet we didn't succeed: ultimately we were essentially crushed by our American competitor Airbnb in our home turf - Europe - and we had no choice but to sell ourselves to another American company, Tripadvisor.

Believe me, I've reflected long and hard on how that could have happened. In fact after I left the company in 2015 I even spent 3 months in isolation in the Annapurna mountains in Nepal to reflect full time on exactly that 😅

And I then moved to China, where I spent the next 8 years and where I had the chance to study their ecosystem to understand why they're successful and Europe isn't.

So all in all, I think I have some degree of legitimacy to comment on this topic.

The WSJ article says that Europe lags behind due to the usual suspects, the reasons you constantly hear about: too much regulation, fragmented European markets, limited access to financing, a culture that isn't conducive to the startup grind, etc.

Some of those are true, but imho all are secondary.

Take excessive regulations for instance, which gets mentioned all the time. If they were such a hindrance to startups, why would American startups succeed in Europe - like Airbnb in our case - and European startups not? We all face the same regulations 🤷

Or take fragmented markets. Same question: how could US startups successfully conquer these fragmented EU markets when European startups can't?

Because that's the real elephant in the room, and really the story of the European tech scene since the advent of the internet: US startups have shown a remarkable ability to capture European markets despite the supposed barriers, making many of the "usual suspects" explanations for Europe's tech struggles very unconvincing.

In other words, logically, any explanation where both US and European startups face identical barriers fails to address the fundamental difference in outcomes we consistently observe.

Based on my experience, the key problem faced by European startups can be summarized in one word: patriotism.

There is virtually none in Europe, and more than anything that's what's killing EU startups, or preventing them from developing.

It used to drive me absolutely nuts at HouseTrip. What a startup needs first and foremost, especially a consumer-facing startup like we were, is marketing, to become famous.

At first, when I created the company and before Airbnb was even a thing, I used to pitch the company to the media and the general response I would get was almost one of contempt, as in "why would I belittle myself to write about your startup? And furthermore, who would be stupid enough to stay in an apartment when there are hotels? You guys have no future..."

And then Airbnb got launched and the American media started their thing, hyping the company like it was the greatest innovation since sliced bread, like they were national heroes, giving them hundreds of millions in free publicity.

That's when European media started to take notice. Not of us, god forbid, but of Airbnb. The concept was promoted by Silicon Valley, see... so now it was valid.

So I went back to pitch HouseTrip to European media. This time around I was met with a different kind of contempt: "So you guys are like Airbnb? Why would we cover a European copycat when we can just write about the real American original?" Luckily I'm not violent but lets say those moments really tested my civility 😅

All in all, we arrived in the absolutely grotesque situation where, despite Airbnb not having yet set foot in Europe, they were already a cultural phenomenon there, promoted by European media, for free, when the European original - yours truly - had to spend millions on paid marketing (mostly to Google and Facebook, American companies) to achieve a small fraction of the brand recognition.

Which means that, insanely, Airbnb was probably doing more business in Europe than we did before even opening an office there, simply on the back of the free publicity they were getting. How on earth can you even compete with that?

This dynamic was at play with general European elites too. I remember very clearly having dinner next to a legendary European entrepreneur and investor - who I won't name, a man who supposedly, on paper, is dedicating his life to furthering the European tech ecosystem. We naturally got to talk about HouseTrip and he literally told me, and this is an exact quote: "you know I don't really like copycats, they really hurt the European ecosystem." Another big test for my civility that night...

And even if we had been a copycat, so what? That's how China got started, there's nothing to be ashamed of. You need to learn to walk before you can run.

In fact if you study the history of innovation you'll find that every major tech power, including the US, started by imitating and adapting others' innovations before developing their own.

Speaking of China, again a country that I know in depth for having lived there for 8 years after HouseTrip, I've come to the conclusion that patriotism, a deeply rooted mindset of sovereignty, is truly the magic ingredient behind their success.

Contrary to popular belief, they don't do it in a stupid way by just banning competition. Those cases are actually very rare and only occur if the companies in question violate Chinese law in pretty egregious ways.

Most of the time it's the exact contrary: they welcome foreign companies and competition, but create conditions where local alternatives can thrive alongside them, giving Chinese users and businesses legitimate options to choose domestic champions.

Which means you end up with, for instance, Apple doing well in China but simultaneously allowing the rise of Huawei or Xiaomi. Or Tesla doing well in China but simultaneously allowing the rise of BYD or Nio. Etc.

And China is, interestingly, more comparable to the EU than most people realize. It is, again contrary to popular belief, extremely decentralized when it comes to doing business, with various provinces competing against each other much the same way EU countries compete against each other.

But they do it in such a way where, again, the overarching sense of Chinese sovereignty never gets sacrificed at the altar of provincial competition. And where the ultimate goal is to develop Chinese champions which can successfully compete on the global stage.

So there you have it, the dirty little secret behind Europe's lag. We're essentially witnessing a "colonization of the minds" whereby Europe has structurally internalized its technological inferiority, celebrating American startups while dismissing its own homegrown companies.

Why does this barely ever get talked about? Think about it: do you seriously think that the Wall Street Journal would start advocating for, essentially, policies hostile to American tech dominance?"

Much better to focus on the usual red herrings like too much regulation or fragmentation which, conveniently, would primarily result in clearing obstacles for American tech giants to dominate European markets even further, rather than nurturing homegrown competitors. This article is, in itself, an illustration of the "colonization of the minds".

Tuesday, February 25, 2025

Friday, January 31, 2025

Beyond geopolitics: Agency and modularity in mobile telecommunications in Kazakhstan

O. Baldakova, E. Oreglia, here.

Thursday, January 30, 2025

Thursday, November 11, 2021

Wednesday, November 03, 2021

Wednesday, September 15, 2021

Friday, March 26, 2021

Wednesday, December 30, 2020

Monday, December 07, 2020

Wednesday, November 25, 2020

Tuesday, November 24, 2020

-

Aka " From Digital Feudalism to Digital Sovereignty " - UCL IIPP, blog and video here. First of all, I strongly recommend watching...

-

Fresh off the press release: the Italian antitrust authority has knocked — quite literally — on Meta’s door. A dawn raid hit the company’s ...

-

M. Kirkwood, here.

-

PR, here . Will we see more DSA and DMA action before the summer break?

-

Details will matter... U. Leyen (von der), here .

-

Podcast with M. Mazzucato, here.

R. Benjon

R. Benjon